"Barney! I yelled irritably at my dog, giving him a firm push with my hand. "Get out of the way." He regarded me with soulful eyes, then dashed off to more peaceful quarters in our house.

It was Saturday, 5:00 a.m., and the Hollywood sky outside my bedroom window was still pitch-black. I was hurrying with last-minute packing for an out-of-town weekend promotional trip for "Little House on the Prairie." I disliked packing. And I was tired of these trips, too, with their non-stop schedules of interviews, luncheons, autographs and photo sessions. It seemed I never got to see my friends anymore. All I ever did was work.

"Missy'" yelled my mom. "Time to go'"

"Okay, okay," I muttered, struggling to zip my bulging carry-all. Slinging the bag over my shoulder, I glanced around the room to make sure I hadn't forgotten anything. My blow-dryer was still lying on the vanity.

"Darn." I let the bag drop to the floor, and walked across the room to pick up the missing item.

"Missy!" Mom was standing in the doorway. "What are you doing? If you don't hurry up, we'll miss the plane'"

Dryer in hand, I glared at her.

The hurt look that crossed her face made me feel terrible, but I just couldn't bring myself to apologize.

"I'll meet you in the car," said Mom quietly. She turned and left the room.

Stuffing the dryer in the bag, I felt my throat tighten with frustration and anger.

Lately, nothing had been going right.

Gossip magazines were printing silly stories about me and anyone they could think of. And because of my age-15-I'd been turned down for a realty good TV role in favor of an older actress who was legally allowed to work beyond an eight hour day. Then, there were always these trips.

But these, I knew, were just surface annoyances. Deep down inside, what was really bothering me was the drastic change being written into my television role as Mary Ingalls, the oldest daughter on "Little House on the Prairie." In a special two-part program, the last two shows of our fourth season, Mary was going to go blind. But that wasn't all. For as long as the series lasted, she was to remain blind. Shooting was scheduled to begin in a few weeks, and I was dreading it.

It wasn't the script that had me worried -I had read it, and it was good. (Mary would eventually learn to cope with her affliction and go on to meet her life-long goal of becoming a teacher.) What I wondered was: What will happen after the first show? I mean, what more could Mary do than be a sort of silent, sad background character? After all, the girl was blind.

Over the weekend, I couldn't stop thinking about the matter-and the more I thought about it, the more my resentment and bitterness grew. Acting is what I love more than anything else. I just didn't understand how, in the long run, this turn of events could help my career.

By the time I returned home on Sunday evening, it was clear there was only one thing for me to do: Through research and study, I would prepare for the role professionally. I would do my best to accurately portray a blind person down to the most minute detail. I would be perfect.

With this in mind, I picked up the phone and made an appointment to visit the Foundation for the Junior Blind in downtown Los Angeles.

The following Saturday was a beautiful day - sunny and warm - but I was a bundle of discontent as Mom drove me to the Foundation. All my friends were at the beach, shopping, having fun-while I would be spending the morning in a dull institutional classroom.

I was greeted warmly by one of the foundation teachers. I explained that I was interested in technical information only-that is, how to sit, stand, walk, eat like a blind person. So the instructor kept her approach straight-forward, matter-of-fact.

"When you sit," she said, "take time to reach out and make sure the chair is there. Then, sit on your hand. It's a small thing, but it's something every' newlyblinded person does."

"Good," I said, "that's just the kind of detail I'm looking for. Viewers will know I've done my research. "

Giving me a rather odd glance, the instructor continued. "When you stand," she said, "brace yourself before attempting any forward movement. You will shuffle at first. Later on in the program, when you've learned to use a cane, you will walk with confidence."

"Great," I said glumly.

"Any questions so far?" asked the instructor, interrupting my thoughts. Her eyes searched mine, as though expecting something.

"No," I said.

She went on to explain such things as how to pour liquid from a pitcher into a glass without spilling. By placing my index finger inside the glass, I could feel when it was nearly full.

"One more thing," she said, when nearly an hour had passed and I was about to leave. "There's something else I'd like you to do when you go home. I want you to close your eyes - no need to use a blindfold - just close your eyes, and take four steps forward."

"Is that all?" I asked.

"Yes," she answered. "It should give you a small idea of what it's like to be without sight. I think you might be surprised at how it feels."

It seemed rather silly to me, but I promised to try it. Thanking the instructor for her time and help, I left.

That afternoon I was home alone with Barney. Mom had gone shopping. The Southern California sun was streaming in through our living room windows making patterns on the thick brown carpet. The room was bathed in golden brightness. Sunlight danced on the brass and crystal fixtures, burnished the wooden coffee table to a rich walnut. I kicked off my sandals and knelt to the floor to play with Barney, We roughhoused for a while until, exhausted. we both flopped flat on our backs. As I looked up at the ceiling, the air seemed to sparkle with suspended particles of glittering dust. It was such an everyday thing - but so pretty.

My thoughts returned to the morning's visit to the Foundation for the Junior Blind, It seemed remote - so far away. I remembered the instructor's request.

Why not? I thought, standing up and brushing my hands on the back of my jeans. It was a simple enough request.

Facing the window, I shut my eyes. An explosion of colors, swirling and brilliant, took me by surprise. I was "seeing" the light from the window.

Casually, I took a step, and then another-but on the third step I froze. I felt as though I were about to fall off a cliff. The room seemed to have dropped away from me; I was alone and facing nothingness-with nothing for support.

Incredulous, I sank to the floor and opened my eyes. The room returned, reassuringly warm and cheerful, bathed in color and light.

I was limp-overwhelmed by the experience. How I had underestimated the enormity of blindness and, at the same time. the powerful accomplishment of any person who has faced and overcome such a handicap. Talk about blind-if anyone was blind, it had been me. I felt sick with shame for my hard heart. The instructor at the foundation had read my lack of compassion like a book. I would have to return and speak with her again. There was much to talk about, much to learn.

Suddenly, the things that had seemed so troublesome to me-the gossip magazines, the lost roles, the inconvenience of out-of-town trips were reduced to trivia in light of the overwhelming sense of gratitude I felt for the blessings in my life. Not only was I thankful for my sight, but for my family, friends, career, and especially - my ability now to bring to the role of Mary Ingalls the courage, confidence and strength that rightly belonged to her. Any fears or doubts I had about Mary's potential as a vital, involved character had dissolved.

"Thank You, Lord," I whispered, "for all You've given me. Help me always to focus not on the dark side of life's little problems-but on the bright side of Your wonderful blessings!"

Barney came over and nuzzled me under the elbow. I held him tightly. We had been sitting like that for nearly ten minutes when Mom came home.

"Missy?" she said, wondering what I was doing sitting in the middle of the living room floor. Curious, she came over and sat down next to me.

"You all right?'" she asked.

"Yes," I answered-and before I knew it, I was blurting out all that had happened, all I'd been thinking about. I apologized for the many times I'd been so snappy and disagreeable for no good reason. Then we hugged each other real tight. I guess Mom and I got a little choked up-until Barney's attempts to get into the act set us off giggling. It was a very special moment.

Well, I'm 17 now - and I know I still have a lot of growing up to do. But thanks to Mary Ingalls and one sunny afternoon, I think I'm off to a pretty good start.

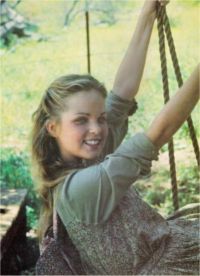

By Melissa Sue Anderson